-

Fibrous thickening of the pericardium forms a rigid, noncompliant encasement of the heart, resulting in progressive impairment in cardiovascular filling and low cardiac output.

-

The pericardium is thick and can’t stretch (less compliant) during diastole

-

The rigid cardiac encasement isolates the cardiac chambers from swings in intrathoracic pressure

-

Inspiration → ↓ in intrathoracic pressure is not fully transmitted to the cardiac chambers b/c they are encased in the rigid pericardium

-

More commonly will follow bacterial pericarditis

- risk of progression is especially related to the etiology: low (<1%) in viral and idiopathic pericarditis, intermediate (2-5%) in immune-mediated pericarditis and neoplastic pericardial diseases and high (20-30%) in bacterial pericarditis, especially purulent pericarditis

-

Characterized by impaired diastolic filling of the ventricles due to pericardial disease.

- constriction limits the total volume of blood that can be accommodated by the heart during diastole across the respiratory cycle, with equalization of right- and left-sided cardiac filling pressures. 1

-

Classic clinical picture: Si/Sx of right heart failure and impaired diastolic filling d/t pericardial constriction with preserved right and left ventricular function in the absence of previous or concomitant myocardial disease or advanced forms.

- Can have hemodynamic impairment if systolic dysfunction d/t myocardial fibrosis or atrophy (more advanced cases)

-

History: fatigue, peripheral edema, breathlessness and abdominal swelling

-

:⚠️Although classic and advanced cases show prominent pericardial thickening and calcifications in chronic forms, constriction may also be present with normal pericardial thickness in up to 20% of the cases

-

Kussmaul’s sign

- Increase in JVP with inspiration

- Inspiration → Increased IVC flow + Increased SVC flow → flowing into high pressure RA → increased JVP w/ inspiration

-

Respirophasic hemodynamic augmentation

- Expiration → rise in intrathoracic (and ∴ pulmonary venous) pressures → ↑ flow into the L heart → b/c it is within a fixed total intrapericardial volume, the increased L heart filling pushes the IV septum towards the right → reduced RV filling → expiratory diastolic flow reversals are transmitted back to the IVC and hepatic veins.

-

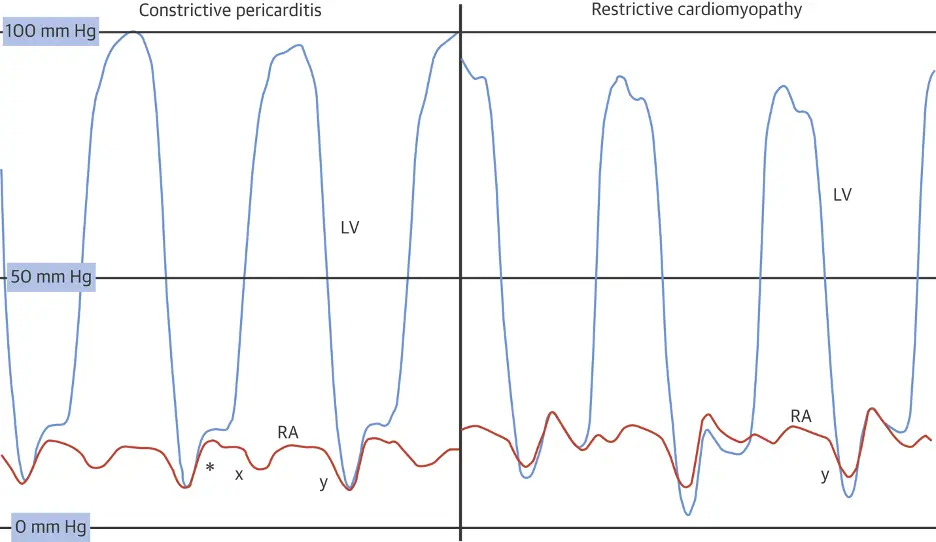

Hemodynamics

- Accentuated rapid ventricular filling

- d/t high atrial driving pressures and unimpeded ventricular relaxation

- Followed by rapid “y” descent, which represents sudden rapid rise in pressure from pericardial restraint

- Exaggerated “x” descent d/t an exaggerated ventricular longitudinal contraction

- ==High diastolic pressures with a paradoxically low SV d/t low preload.==

- Classic appearance:

- Rapid “y” descent on atrial pressure waveform

- “Square root” sign on ventricular pressure waveform

- Accentuated rapid ventricular filling

Caption: (Left) Left ventricular (LV) (blue) and right atrial pressure (RA) (orange) hemodynamic pressure tracings in constrictive pericarditis (CP). Prominent “x” and “y” descents are present with a square root sign (*). (Right) LV and RA pressure hemodynamic pressure tracings in restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM). A prominent “y” descent is present, but the “x” descent is blunted. (Figure source: 1)

Caption: (Left) Left ventricular (LV) (blue) and right atrial pressure (RA) (orange) hemodynamic pressure tracings in constrictive pericarditis (CP). Prominent “x” and “y” descents are present with a square root sign (*). (Right) LV and RA pressure hemodynamic pressure tracings in restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM). A prominent “y” descent is present, but the “x” descent is blunted. (Figure source: 1)

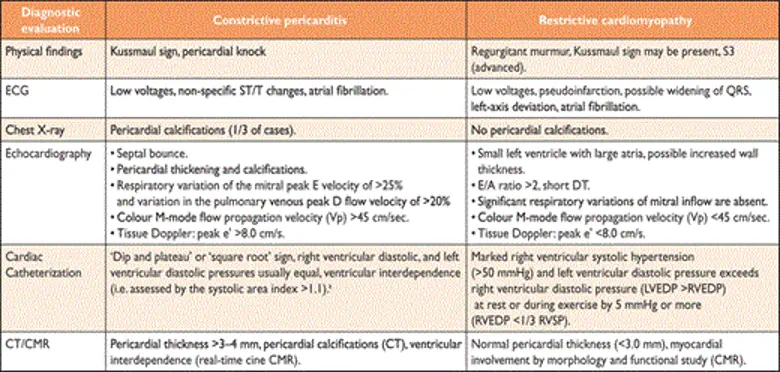

- Main DDx is restrictive cardiomyopathy

- Constrictive pericarditis (CP) is a potentially reversible cause of heart failure, whereas restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) has very limited therapeutic options. 1

- Restrictive cardiomyopathy is primarily a disease of the myocardium and is characterized by increased myocardial stiffness, which results in a rapid rise in ventricular filling pressures reflected in both the systemic and pulmonary circulations 1

- Abnormal diastolic dysfunction, but preserved LVEF

- Amyloidosis is the most common secondary form of RCM

- Treatment is often limited to heart transplantation

- The utility of CMR in constrictive pericardial disease is well established, providing the opportunity not only to evaluate pericardial thickness, cardiac morphology and function, but also for imaging intrathoracic cavity structures, allowing the differentiation of constrictive pericarditis from restrictive cardiomyopathy. Assessment of ventricular coupling with real-time cine magnetic resonance during free breathing allows an accurate evaluation of ventricular interdependence and septal bounce.

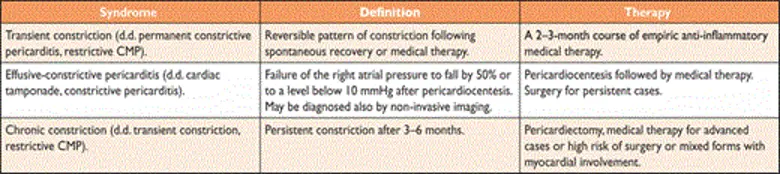

Flavors of constriction

- Chronic constriction

- Transient constrictive pericarditis

- usually develops with pericarditis and mild effusion and resolves with anti-inflammatory therapy within several weeks

- Constriction is d/t inflammation → resolves w/ Tx of the inflammation

- Effusive-constrictive pericarditis

- pericardial cavity is typically obliterated, i.e. even the normal amount of pericardial fluid is absent

- Scarred pericardium 1) constricts cardiac volume and 2) can put pericardial fluid under increased pressure (→ signs of cardiac tamponade)

- Causes include idiopathic, radiation, neoplasia, chemotherapy, infection (especially TB and purulent forms) and post-surgical pericardial disease

- Clinical features of pericardial effusion or constrictive pericarditis, or both

Diagnosis

- Echo, CT (with contrast enhancement to assess pericardial inflammation), CMR, Cath

- Since the inflamed pericardium is enhanced on CT and/or CMR, multimodality imaging with CT and CMR may be helpful to detect pericardial inflammation. Can be useful to see if you’re dealing with transient constrictive pericarditis.

- Specific diagnostic echocardiographic criteria for the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis has been proposed by the Mayo Clinic and include:

- septal bounce or ventricular septal shift with either medial e′ >8 cm/s or hepatic vein expiratory diastolic reversal ratio >0.78 (sensitivity 87%, specificity 91%; specificity may increase to 97% if all criteria are present with a correspondent decrease of sensitivity to 64%

- ‘End-stage’ constrictive pericarditis

- Manifestations include cachexia, atrial fibrillation, a low cardiac output (cardiac index <1.2 l/m2/min) at rest, hypoalbuminemia due to protein-losing enteropathy and/or impaired hepatic function due to chronic congestion or cardiogenic cirrhosis.

Management

- 📝 in the absence of evidence that the condition is chronic (e.g. cachexia, atrial fibrillation, hepatic dysfunction or pericardial calcification), patients with newly diagnosed constrictive pericarditis who are hemodynamically stable may be given a trial of conservative management for 2—3 months before recommending pericardiectomy. This is b/c it may be transient constrictive pericarditis and could resolve with Tx.

- Surgery

- Pericardiectomy is the accepted standard of treatment in patients with chronic constrictive pericarditis who have persistent and prominent symptoms such as NYHA class III or IV.

- Patients with ‘end-stage’ constrictive pericarditis derive little or no benefit from pericardiectomy, and the operative risk is inordinately high.

- Predictors of poor overall survival are prior radiation, worse renal function, higher pulmonary artery systolic pressure, abnormal left ventricular systolic function, lower serum sodium level and older age.

- 📝 Pericardial calcification had no impact on survival.

- Complete surgical removal of the pericardium can result in excellent symptomatic improvement. The prognosis is dependent upon the underlying etiology, with prior radiation therapy consistently associated with worse outcomes

- Pericardiectomy is the accepted standard of treatment in patients with chronic constrictive pericarditis who have persistent and prominent symptoms such as NYHA class III or IV.

- Medical therapy has a role in 3 cases:

- Specific etiology, such as TB pericarditis, to prevent progression to constriction

- Transient constriction d/t pericarditis — gets better as you Tx the pericarditis

- Supportive — control Sx of congestion in advanced cases or when surgery contraindicated/high-risk